Field notes on Othering: A critique of Soham Gupta’s photobook ‘Angst’

Handmade edition of the photobook, Angst. Used with permission of the artist.

Co-authored by Adira Thekkuveettil and Amarnath Praful

Soham Gupta’s photography project Angst has seen a meteoric rise in recent times in the fine art photography world. Over the last two years, the work and the resulting book (published by Akina Books) have been included in major exhibitions at Les Rencontres d’Arles, Paris Photo, and most recently the 2019 Venice Biennale. At face value, Angst is a work of photography and text. The photographs are mostly portraits of people, many of whom seem unsheltered and living in very precarious circumstances on the streets of Calcutta (officially known as Kolkata), interspersed with images of the city at night. Its text reads like a tragic opera composed in prose and poetry, witnessed through the eyes of one omnipresent narrator figure who experiences the city at its darkest.

We first came across an early version of Angst at the 2015 Delhi Photo Festival and, at the time, found the lack of available critique around it disturbing but not too surprising. Then, as now, there are barely any mainstream platforms that give space to or promote alternative voices in criticism on photography in India. What has been more disappointing in the years since this work has come out is the art world’s continued reluctance to engage in any kind of nuanced critique, coupled with active resistance to any form of criticism at all.

At the outset, we want to make clear that we do not advocate ideas of censorship or moral policing of any work. We are also not privy to the internal agreements or relationships that Gupta has with his subjects and do not wish to speculate on them. Regardless, Gupta did have a large (if not complete) role in the manner of their portrayal. We also understand that Angst is not the only photographic work with problematic representations and ethical concerns currently in the spotlight. Rather we look at this work as a symptom of a larger ongoing system of questionable practices of representation which have long been prevalent in the subcontinent.

To construct a nuanced critique around the work, we need to trace our examination from the colonial camera’s gaze up to the systems in which the work currently exists and disseminates. The point of the critique is to perhaps raise questions and encourage a discourse rather than to provide tailor-made solutions.

The Colonial Ghost

The camera, wielded as a weapon of the colonial empires, has taught us how to see, to stare, and to tell stories. … What we don’t want to acknowledge is that the colonial ghost is still present in our own gaze, both as creators of work as well as audiences.

The Indian subcontinent has been the camera’s subject since the birth of photography. The camera, wielded as a weapon of the colonial empires, has taught us how to see, to stare, and to tell stories. It also easily tricks us into believing that only those of us who hold the camera has the power or sometimes even the right to depict. But the camera is only a tool. Can the problem of objective representation not be solved by simply handing the camera over to the erstwhile colonised subject? Not always, as the photographer still has to grapple with two of the more insidious ideas of the colonial project: The Other and The Gaze.

The Other of the mysterious Orient was already created, gazed at, lusted after, and despised in western literature and painting long before photography was even born. But like the other marvellous inventions of the industrial revolution, photography collapsed time and distance, thus accelerating the speed of dissemination and consumption of the imagined Other. Yet even within colonial photography, this imagination existed in a hierarchy of caste, gender, and class, erasing agency by layers. In India, those at the top of the hierarchy were photographed with more dignity — as individuals. As one went down the ladder, the subject increasingly became a body, a specimen, or a type, and agency ceased to exist. These photographs would usually be constructed around how the photographer chose to imagine his subjects, without much regard for actual contexts. The accompanying text would often give information of categories like body measurements, occupation, religion, and caste, along with other observations made by the (usually) European ethnographer.

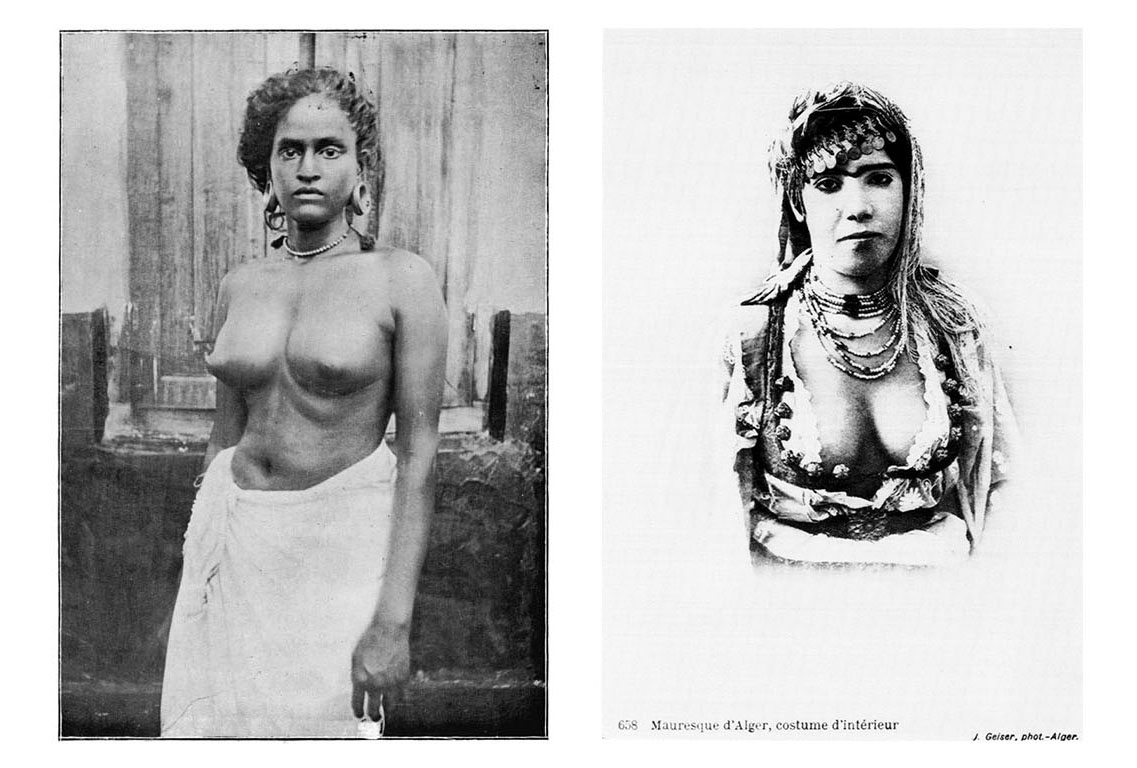

The market for photography of the colonies, much like prize hunting, rewarded this white male persona. Lauded as the explorer and adventurer, the narrative usually centred around their tales of fantastical experiences in distant lands, with the photographs serving as trophies. These images were greedily collected back in Europe both in beautiful folios, as well as cheap postcards. Most popular, of course, were images of women. From Thiyya women in Kerala to staged photographs of women in Algeria, these pictures were made and consumed as sexual fantasies, disguised as an ethnographic study. The original subjects of the photographs in most cases never got to see their images or even know how they were being disseminated. The power and pleasure of viewing the photograph were strictly reserved for those in the upper layers of the colonial order and almost entirely excluded the subject.

Left: Photograph of A Thiyya woman from Castes and Tribes of Southern India, by Edgar Thurston. Published by Government Press Madras, 1909.

Right: Photograph of an Algerian woman from The Colonial Harem by Malek Alloula, translated by Myrna Godzich and Wlad Godzich. Published by the University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

By the latter half of the 20th century, the job of the heroic ethnographer fell to an eager breed of photojournalists who, facilitated by their editors, publications, and consumers, carpet-bombed the world with the exact same image of the Other. Fortunately, though, the criticism around this imagery has only gotten louder and more articulate as the decades have passed. National Geographic magazine’s apology in 2018 admitting that their coverage was racist and exotic for the past several decades was one of these landmarks. Now, we like to believe that blatant orientalist & racist imagery is largely considered to be unfashionable, although we still get examples of it every couple of years to remind us that nothing has changed.

What we don’t want to acknowledge is that this ghost is still present in our own gaze, both as creators of work as well as audiences. The colonial ghost continues to haunt us in more ways than one. We sense it yet we doubt whether we can accurately place it within our own radar. Many reviewers of Angst felt the need to categorically state how, normally, the aesthetics of the work would fall into the dreaded realm of exploitative voyeuristic photography, but that somehow it is all redeemed since Gupta is seen as an insider, the photographs are staged, and made in supposed collaboration with all his subjects. Reviews also cite the use of text in the work as humanising, even though all the stories in the book have been written singularly through the photographer’s positioning and point of view. So, by virtue of the stage and use of fiction, we are back to the brave artist figure confronting what we would otherwise not see.

The murky swamp of Consent, Collaboration, & Agency

In a 2016 interview, Gupta stated that he spent a ‘long time’ getting to know his subjects before he photographed them and that most of them ‘performed’ for him in front of the camera. If this is then a fiction, staged and dramatically lit to show us the dark underbelly of infamous Calcutta, then are his subjects actors/models? No, they clearly are not; at least not most of them.

At this point, we need to split the portraits in Angst into two distinct categories. The first kind is the images of people who actually do live on the margins. They make up the majority of photographs in the book. Many of these people seem to be homeless, and barely surviving amidst daily violence and repeated injustice. Several of them are clearly suffering from physical, emotional and mental trauma. The images have been made at night, with a harsh flash revealing the bodies of his subjects while largely erasing background context. The backgrounds according to Gupta have been intentionally stripped away in order to turn the street into a studio. Once again, only their bodies matter, almost as a typology. Their voices are replaced by the stories the photographer wants to tell. Although a few of the photographs, like the one on the book’s cover, do perhaps display tenderness and active participation, this does not seem to be the case for a majority of the images.

Photograph from Angst. Used with permission of the artist.

If an image is considered art, is it automatically insulated from any consequence or ethical responsibility?

The central premise of the work, that it is performative and collaborative, often falls apart, especially in the case of the photograph of a man, eating from a pile of domestic refuse on the side of a road. That image is not staged (as clarified by Gupta on an Instagram post with the same image). There is no collaboration there. It is simply further violence and indignity on a man trying to survive. This human being has been easily reduced into a one-dimensional symbol for some undefined ‘Angst’ with no follow-up or actual interaction in the book. The photographer’s flash reveals him to us, yet completely blinds us to him as a person. As an audience, it is presumed that we need to know nothing more about him apart from what this one image represents. Does the critique against Alessio Mamo’s use of Indian children as symbols for an abstract concept not apply in this case simply because Angst is deemed as ‘art’?

The second kind of photographs in Angst (a total of 4 in the book) were originally part of a commissioned editorial which Gupta photographed for the ‘Style’ section of the Indian magazine Platform, in its January — February 2018 edition. They employ the same visual formula of the flash at night on the street, except the subjects here are models, dressed in high fashion, mimicking the aesthetic of Angst. One image shows a young person named Kupu, described as a fashion student, whose designer clothes and accessories are carefully detailed in the accompanying caption (this information is only in the magazine spread and not in the book). Kupu is seated next to an old man on a bed inside a section of concrete pipe. The pipe appears to be the man’s home. The old man is not named or alluded to in any way at all in the editorial. There, he is simply a prop along with the bed and the pipe.

In Angst, the book, absolutely no context at all is given in the text for this or the other three editorial images being included. No story of a Gucci sporting kid in the big, bad city. Why not? Would that be taking something away? Do these commissioned pictures — originally made as advertisements for designer clothes, put together by a paid team of stylists, makeup artists and models really represent the same kind of ‘Angst’? Gupta has also not mentioned anything about the nature of the collaboration between the models and his primary subjects. Without any context, only a shared fetishistic aesthetic seems to decide that the editorial images and photographs of people in the street could be grouped together.

Gupta has acknowledged the literature of Hubert Selby Jr and the photographic work of Antoine d’Agata to be major influences in his practice. Although there is a difference between writing fiction and using photographs of actual marginalized people to construct a fictional world, it does present an opportunity to inquire into broader questions of how the production, appropriation and consumption of the marginalised in writing and art are often done while maintaining hegemony. While Selby’s portrayal of dark and grim Brooklyn was done via literature, d’Agata used real systems of sex trafficking, drug abuse, and violence to construct his photographic oeuvre. Those people are not characters who only exist on a page. And using them as props or symbols to illustrate abstract concepts of personal angst is a continuing and unchecked form of violence.

If an image is considered art, is it automatically insulated from any consequence or ethical responsibility? Let us assume that all the subjects in Angst consented to be photographed. How many of them are aware of how their photographs have been disseminated, in what contexts they have been published, and which story has been printed next to them? Do most of them even have access to see their own images in this work? And even if they did have the access, do they have the immense privilege to be lettered specifically in English, in order to comprehend how the accompanying text paints their lives? Does it even matter in this case, since this work is exclusively marketed to an unimaginably elite art world? The positioning of Angst ensures that the world Gupta depicts through this work is only ever meant to be consumed in one direction.

The subject’s own story can all too easily be ignored or even discarded by a photographer in an attempt to turn them into symbols and make them fit the desired narrative. Recent research into two of the most iconic photographs of all time, Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother and Steve McCurry’s Afghan Girl has revealed that in both cases the subjects, Florence Owens Thompson and Sharbat Gula, — both of whom remained nameless for much of their lives — have had a painful and complicated relationship to their famous photographs.

At Art Basel this year, the artist Andrea Bowers used images & stories of survivors of abuse in an elaborate work on the #MeToo movement, without asking for any form of consent from those survivors. Thanks to social media platforms, some of these survivors became aware of their photographs being used in the work. The artist was then publicly called out and had to remove those images from the show. Would most of the subjects of Angst ever have the power to remove their images from the Venice Biennale if they so wished? The answer is clearly No.

Let’s address the muse.

“But our Calcutta, this crumbling city, it echoes with the cries of pain and the howls of agony…”

- Gupta on Angst

The city of Calcutta as the muse is central to the narrative of Angst. The repeated allusions to ‘this crumbling city’ is a deeply familiar analogy to most people who have heard of Calcutta due to a three hundred year history of unbroken usage. Floating like a film of oil above the city, this image has slithered into our psyche so deep that it’s all we want to see when we think of Calcutta. Ever since the day Job Charnock and his motley crew from the East India Company first pitched their tents on that particular bank of the Hooghly river, the image of the city that since emerged has oscillated constantly between being a site of colonial glory, as well as a swamp of tigers, death and disease. Of course, this oscillation of imagery was almost exclusive to European writings about the city; Bengali accounts from the same time offered vastly different perspectives, but they did not gain a wide readership or promotion beyond Bengal.

A 2018 review of Angst by Sukhdev Sandhu begins with quotes by Thomas Macaulay and Rudyard Kipling (both committed racists and imperialists of the 19th century), with Kipling deeming Calcutta, ‘one of the most wicked places in the universe’. Very quotable and fitting at first glance. Funnily, Sandhu’s 2013 review of Amit Chaudhuri’s Calcutta: Two Years in the City uses the same exact opening quotes, because it seems one work on Calcutta is equal to any other work on Calcutta and stock lines are just easy. Just like stock quotes, stock images of the city are also abundant, constantly replenished by several generations of photographers who simply want to depict, represent and show the world, without ever sitting down to examine their own privilege.

This examination would no doubt be an uncomfortable exercise, as pretty early in the process, one would have to confront one’s own complicity in the systems that profit from poverty, inequality, and injustice. These systems do not exist in isolation. Vested interests have been profiting and continue to profit from Bengal being systematically bled since the time of the East India Company and the British Raj. The 20th century in Bengal — and later West Bengal — has been defined by a devastating man-made famine, a traumatic partition, the repeated arrivals of millions of refugees, as well as significant political resistance movements that have been severely quashed by the ruling governments. Extreme rural poverty, inequality, caste and religious violence (often gendered), have forced generations of migrants to continually flee to the city of Calcutta where they then barely manage to survive.

Like any city, anywhere, Calcutta too was built on and functions on the backs of the marginalised. Its own government, businesses, infrastructure and citizens continually rely on hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children who are living in a state of constant precariousness to provide the city with dirt-cheap labour, often with no rights, and in dangerous circumstances. They are disposable and then rendered invisible only when it is convenient. And they are deemed ‘voiceless’ by those who turn a deaf ear to them, the powerful among whom otherwise find much benefit in coercing and manipulating their voices for political gain. Those of us who have the privilege to assume they are invisible to us unless represented, are complicit in the oppression. Always.

“At times, Calcutta seems to be the bleakest of all places. The city, like that forgotten pot of tea, feels so bitter, the tea-leaves resting in the teapot’s womb — like your love for Calcutta — responsible for all the bitterness.”

- Gupta on Angst

Although Angst’s text wants to address the cruel irony of life in the city, it unfortunately still leeches off of Kipling’s City of Dreadful Night imagery. In the world of Angst the people at the bottom, like Yadav the Puchka seller or Swapan the parking-fee collector are assumed to not be bitter. They don’t get to have the awareness or consciousness to know of systemic inequality or oppression. Swapan is in fact compared to a lamb about to be slaughtered, who has no idea what’s really going on. Things simply happen to them. Only Gupta’s narrator has the hyper-awareness to see through it all.

The text also periodically switches between the voice of a narrator/observer to the inner voices of the characters themselves. Although a common literary tool, in this text the timing of the switches back to the narrator is careful; done at crucial moments when the narrator wants to walk away and take the story with him. This is telling on both the artist and us as a society; we are habituated to flitting in and out of the lives of the marginalised, co-opting and scavenging parts of their stories while centring the narratives on ourselves. Combined with the edit and strategy of the images in the book, his characters become particularly one dimensional; existing only in the shadow of the night and the specific circumstances into which the text places them.

Hitting your head against glass walls

The photographers’ relations to power have too often relegated the subaltern or the less privileged to a space of performance without agency. … The history and ethics of representations have to be taken into account when making work because they have real-world political consequences.

The beautifully printed photo book, its £40 price tag (£60 for the special handmade edition), the exhibition in the centre of the European art world at the Venice Biennale, the website, and even social media all cater to a social class which completely excludes most of the subjects of this work. On the surface, Angst simply joins the hundreds of other such work made in and about cities like Calcutta. What is more in need of inspection is actually the intricate binding of the systems that validate work of this nature, and ship it off to global pedestals in order to be admired without anyone raising an eyebrow or having a real conversation about the work’s implicit message, or its impact within the environment where it was made. These pedestals seem to have the exclusive power to determine how work must be read, and which works then become valuable.

A continuing colonial gaze, combined with curatorial laziness works to bypass real contexts of historical, regional and socio-cultural nuances in the validation and dissemination of works from the Indian subcontinent. The assumption that Soham Gupta’s work is free of this gaze because he is from Calcutta is a gross overlooking of the class, caste, religious and gender hierarchies that divide the everyday Indian experience. The photographers’ relations to power have too often relegated the subaltern or the less privileged to a space of performance without agency.

Even within Europe, works that were built on exotic and stereotypical representations of other European cultures have recently been criticized. Swiss artist Romain Mader’s work ‘Ekaterina’ which won the Foam Paul Huf award in 2016, was critiqued extensively because of the work’s inherent ties with stereotyping and objectification of Eastern European women. To reiterate, the ability to look upon one’s subjects as Other is not simply a geographical, historical or racial privilege exclusive to white artists training their lens on non-white subjects. It is a far more complex and uncomfortable terrain where historical, economic, class, caste and gender privileges all play a part in determining who has the power to depict and how.

Considering that there is already growing, visible, and valuable criticism around many white artists and their work, it seems unfair to exclude the work of artists of colour from this conversation. Concentrating criticism around white artists (although important) reinforces the idea for the larger audience that the work of non-white artists are largely meant for passive consumption and token appreciation, while white artists get to have their work seriously considered, critiqued, and actually talked about. It further discourages us as brown audiences from training a critical eye on one of our own for fear that the little representation that non-white artists receive on global platforms will somehow be tarnished.

Concentrating criticism around white artists reinforces the idea for the larger audience that the work of non-white artists are largely meant for passive consumption and token appreciation, while white artists get to have their work seriously considered, critiqued, and actually talked about.

There are several glass walls between the photographic subject’s own experience, the imagination of the subject through a camera, and the circulation of the work within a global market. There is an illusion of transparency, but these systems are still very much opaque. A work like Angst which contextualizes a reality into an artistic endeavour comes with many challenges, questions, and possible problems. The insular systems that disseminate and dictate photography and art puts the emphasis on the maker and rarely the subject. Angst’s photographic subjects remain nameless, without a claim to their own individuality, and continue to be relegated to a stereotypical imagination, while the artist’s right to subjectivity, to depict, and to write about them as he chooses remains upheld.

The thesis of Angst actively traps its subjects in the triad of sex, hunger, and violence, with no other possible reality. This narrative too easily falls in line with the ‘mainstream’ culture of the subcontinent, where the marginalised are at worst used as objects of mockery and derision and at best are props for performing benevolence. Even if it is assumed that an artist may not be aware of how their work further propagates a trope, that ignorance does not become a reason to not critique it. Although it is important that photographers and artists engage and make work with and about all kinds of communities, and address serious issues both through art-making as well as journalism, their methods of representation can and must be thought of with more care, respect, and awareness, especially in an era when images are more powerful and have a more direct impact than at any previous time.

The history and ethics of representations; the nuances of class, caste, gender, and geopolitics; consent and collaboration all have to be taken into account when making work because they do have real-world political consequences. Art cannot and should not solely exist in an elite vacuum. This responsibility is not simply on artists but perhaps more importantly on the curators, publishers, juries of prestigious awards and us the audience, who all define the voices of the time. A more nuanced, informed, and critical understanding is absolutely essential in the photography and art world. This system is still very much controlled by a minuscule group of people holding largely Eurocentric and colonial views of the subcontinent. Along with more artists of colour, space has to be made for more independent discourse, dialogue, critique, and many many more diverse voices to engage with the world of art so that it may actually grow and evolve more inclusively.

We can do so much better.